People have always been drawn to the power and beauty of St. Anthony Falls. For Native Americans, the falls possessed religious significance and harbored powerful spirits. For the early European and American explorers, the falls provided a landmark in a vast wilderness, as well as an interesting geological phenomenon. During the 19th century, settlers, tourists and artists were drawn to St. Anthony Falls' picturesque beauty, while entrepreneurs seized the water power of the falls for their lumber and flour mills. Meanwhile, promoters of river transportation viewed St. Anthony Falls as an obstacle to be overcome, as they dreamed of extending navigation on the Mississippi River above Minneapolis.

People have always been drawn to the power and beauty of St. Anthony Falls. For Native Americans, the falls possessed religious significance and harbored powerful spirits. For the early European and American explorers, the falls provided a landmark in a vast wilderness, as well as an interesting geological phenomenon. During the 19th century, settlers, tourists and artists were drawn to St. Anthony Falls' picturesque beauty, while entrepreneurs seized the water power of the falls for their lumber and flour mills. Meanwhile, promoters of river transportation viewed St. Anthony Falls as an obstacle to be overcome, as they dreamed of extending navigation on the Mississippi River above Minneapolis.

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers has played an important role in the history of St. Anthony Falls. In the 19th century, the Corps was responsible for saving the waterfall from destruction. In the 20th century, the Corps designed and constructed the Upper Harbor Project, which extended the Mississippi River's navigation channel over the falls by way of the Lower and Upper St. Anthony Falls locks.

Today, the St. Paul District, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers maintains the Upper and Lower St. Anthony Falls locks and darns.

Geology

Imagine a waterfall 2,700 feet across and 175 feet high with the meltwaters of the colossal Glacial Lake Agassiz pounding over it. Such a waterfall existed about 12,000 years ago near what is now downtown St. Paul. As the water rushing over the valley's bedrock of limestone scoured away the underlying sandstone, large slabs of limestone collapsed into the river, causing the falls to migrate upriver. About 10,000 years ago, this huge waterfall reached the junction of the Mississippi and Minnesota Rivers, and split into two falls. The waterfall that followed the course of the Mississippi River upstream was St. Anthony Falls.

Geology dictated a natural extinction for St. Anthony Falls, for the limestone bedrock covering the soft sandstone ends only about 1,200 feet above its present location. Once the falls reached the end of this protective cap, it would erode into rapids. The limestone bedrock in this area is also relatively thin. At its maximum, the limestone at St. Anthony Falls is only 14 feet thick, compared to the usual 25-foot thickness of the bedrock downstream. Thinner limestone cracked more readily, hastening the demise of the waterfall as it moved upstream. From its origins near Fort Snelling, St. Anthony Falls retreated slowly upstream at a rate of about 4 feet per year until it reached its present location in the early 1800s. Geologists estimate that originally the falls were about 180 feet high. As the waterfall receded, it also decreased in height. In 1680, Father Louis Hennepin became the first white person to encounter the waterfall on the Mississippi River, naming it for his patron saint, Anthony of Padua. Hennepin estimated the falls' height to be 50 or 60 feet. Early 19th century explorers described St. Anthony Falls as being in the range of 16 to 20 feet high.

St. Anthony Falls' retreat upriver was greatly accelerated in the mid-1800s, when settlers began building lumber and flour mills along the waterfall's edge. To supply their mills with water, millers drove shafts through the limestone bedrock and excavated canals in the sandstone underneath. During floods, hundreds of logs escaped from holding ponds and pounded the falls ' edge. Dams built to divert water to the mills left large sections of the limestone dry, exposing the rock to more freezing and thawing, and causing cracking. Water flowed down through the cracks, eroding the underlying sandstone.

With the development of milling, the migration of St. Anthony Falls accelerated to as much as 35.5 feet per year in 1852. Between 1857 and 1868, the waterfall was receding at an average of about 26 feet per year and corning perilously close to the limits of the limestone cap.

General History of St. Anthony Falls

Before Father Hennepin named St. Anthony Falls for his patron saint, Native Americans living in the region had given the waterfall various names. The Ojibway called the falls Kakabikah (the severed rock). The Dakota used the terms Minirara (curling water) and Owahmenah (falling water). For the Dakota, the falls had religious meaning and were associated with legends and spirits, including Oanktehi, god of waters and evil, who lived beneath the falling water.

To European and American explorers, St. Anthony Falls was a landmark in a vast wilderness. In 1683, Hennepin published a book about his travels in America that was widely read in Europe. His description of the beauty and wonder of the waterfall on the Mississippi River made the site famous.

In the 1700s and early 1800s, others came to explore the region and view the Falls of St. Anthony for themselves. Jonathan Carver, a Connecticut colonist, came in 1766 representing Great Britain. Twelve years after his visit, Carver published a book that became a best-seller and included the earliest known sketch of St. Anthony Falls. Carver described the waterfall as "pleasing and picturesque," estimated its height at 30 feet and noted that six islands surrounded the waterfall.

Lt. Zebulon Montgomery Pike was the first American to explore the Upper Mississippi River after the United States acquired the region in the Louisiana Purchase of 1803. In 1805, the federal government hired Pike to lead an information-gathering expedition and to secure permission from Native Americans to build military posts along the river.

Pike described St. Anthony Falls as 16.5 feet high and lacking the majesty he had expected from the descriptions of Hennepin and Carver. Pike did note, however, that at high water, the waterfall "is much more sublime, as the quantity ojwater thenjorms a spray, which in clear weather reflects from some positions the color of the rainbow, and when the sky is overcast covers the falls in gloom and chaotic majesty."

The establishment of Fort Snelling at the confluence of the Minnesota and Mississippi rivers in 1820 attracted many tourists, writers and artists to the region. In 1823, the first steamboat navigated the Mississippi River as far as Fort Snelling. By 1851, St. Paul had established itself as the head of navigation on the river. Tourists disembarked at St. Paul and hired carriages or wagons for sightseeing excursions to St. Anthony Falls, Minnehaha Falls, and nearby lakes.

The development of milling at St. Anthony Falls led to its demise as a tourist attraction. Visitors in the 1850s and 1860s found that the natural landscape of St. Anthony Falls had been altered by the construction of mills, by the noise of mill machinery, and by milling waste products.

In 1862, one visitor complained that, "St. Anthony Falls are all covered with mills and refuse." Johannes Kohl, a German geographer and scientist, described the falls as they appeared in 1856: Walls and dams have been built out onto the falls .... The water being so low, the Mississippi could not carry away the load of sawdust, chips, odds and end of board and plank, and logs dumped in upstream. This industrial waste was stuck everywhere in big jumbled heaps in the falls ' attractive little niches and in the rocky clefts intended by Nature for the joyous downward passage of crystalline waters.

Milling at St. Anthony Falls

While the scenic beauty of St. Anthony Falls attracted early explorers and tourists, it was more important to settlers as a source of water power. Soldiers at Fort Snelling built the first sawmill at the falls in 1821; and, in 1823, added a grist mill. By the 1850s, as many as 16 sawmills crowded the falls. During the 1860s alone, lumber production at the falls increased from 12 million to 91 million board feet. In 1869, there were six sawmills on the east side of the falls and eight on the west side.

During the 1860s, flour milling increased substantially at St. Anthony Falls. Flour production rose from 30,000 barrels in 1860 to 256,100 barrels in 1869. In 1869, there were eight flour mills on the west side of the river and four in St. Anthony. By 1880, 27 mills were producing more htan 2 million barrels of flour annually, making Minneapolis the national leader in flour production. Franklin Steele, a local entrepreneur, obtained much of the land on the east side of St. Anthony Falls in 1838 and constructed a dam and sawmill there in 1848. Steele's dam was located above the edge of the falls. It crossed the east channel and ran from the shore to a short distance above Hennepin Island and then to the foot of Nicollet Island.

In 1849, Steele registered the plat for a town site, which he named St. Anthony. By 1850, more than 600 residents lived in the town; and, by 1855, the population had grown to 3,000.

The land on the west side of the Mississippi River remained part of the military reservation surrounding Fort Snelling until 1852, when Congress reduced the size of the reservation and opened the land for sale. However, commandants at Fort Snelling had been granting permits to allow settlement on the west side since the 1840s, and many other settlers had staked claims without permission. This community, which would later become Minneapolis, numbered only about 300 in 1854, but by 1856 the population had grown to 1,555.

In 1849, Robert Smith obtained a lease to run the government grist mill and sawmill on the west side of the falls. In 1853, Smith purchased the government mills and went into partnership with several others. By 1855, a partnership of 12 men controlled the west-side mills and the adjacent land. However, this group did little to develop water power at the falls before 1856.

In 1856, two companies received charters from the Minnesota Territorial legislature to develop the water power at St. Anthony Falls. The Minneapolis Mill Company, representing west side owners, and the St. Anthony Company, representing the east side, agreed to work together to improve the water power for milling at St. Anthony Falls. The companies cooperated to construct a dam across the river above the falls that divided the flow of water into millponds on the east and west sides of the river. When the project was finished, the two companies had built a single large dam in the shape of a V, which angled out from both shores and met upriver.

The Minneapolis Mill Company quickly moved ahead of the St. Anthony Company in developing ways to distribute water power. The west-side owners built a canal angling inland from the millpond and running along the shore to carry water to numerous mill sites. Beginning in 1857, the Minneapolis Mill Company began excavating the canal, which would be 14 feet deep, 50 feet wide and 215 feet long. The canal was lengthened in later years to accommodate the demand for more access to the water power of the falls.

The west-side water system included smaller canals to carry water from the main canal to the mills (headraces) and from the mills back to the river (tailraces). When the system was completed, the Minneapolis manufacturing district consisted of 2.9 miles of tunnels and open canals.

In contrast to the system developed by the Minneapolis Mill Company, the St. Anthony Company did not build canals to distribute water power on the east side of the falls. Instead, the St. Anthony Company owners relied on shafts and ropes running from water wheels on the dam to supply the mills.

The canal system enabled Minneapolis to quickly surpass St. Anthony in the development of manufacturing at the falls. By 1869, Minneapolis was producing five times as much flour and twice the amount of lumber as east-side manufacturers.

The population of Minneapolis also soon outgrew that of St. Anthony. Between 1857 and 1870, the population of St. Anthony increased by only 324, while Minneapolis grew from 3,391 residents in 1857 to 13,066 in 1870.

The Eastman Tunnel Collapse

The water power companies that controlled the mills at the edge of the falls had forgotten to secure title to Nicollet Island, located a short distance upstream. As a result, in 1865, William Eastman and John Merriam acquired the island. The new owners quickly sued the St. Anthony Company to force the removal of the east-side mills, claiming that the installations infringed on their water rights.

The water power companies that controlled the mills at the edge of the falls had forgotten to secure title to Nicollet Island, located a short distance upstream. As a result, in 1865, William Eastman and John Merriam acquired the island. The new owners quickly sued the St. Anthony Company to force the removal of the east-side mills, claiming that the installations infringed on their water rights.

In 1867, the St. Anthony Company and the Nicollet Island owners compromised. The company was allowed flowage, dam and boom privileges on the island's shore, while Eastman and Merriam were allowed to draw enough water to create 200 horse power for use at their own mills. Unfortunately, the agreement also allowed Eastman and Merriam to excavate a tunnel under Nicollet and Hennepin Islands for their tailrace.

In September 1868, Eastman, Merriam and two additional partners began excavating the tailrace. The plans called for a 6-foot by 6-foot tunnel cut through 2,500 feet of sandstone. Workers began digging at the downstream end of Hennepin Island and by October 4, 1869, they had tunneled through 2,000 feet of sandstone, bringing them as far as the toe of Nicollet Island. That day, however, workers discovered water leaking, and then rushing, into the upper end of the tunnel.

Early the next morning, the river broke through the limestone at the upper end of the project, forming a large whirlpool that sucked everything nearby into the tunnel. The water quickly scoured out the 6- by 6-foot tailrace, enlarging its width as much as 90 feet and increasing its depth to 16 ½ feet. As the roof of the tunnel fell in, Hennepin Island began to sink and the falls were in danger of collapsing.

Almost immediately, word spread through Minneapolis and St. Anthony that the falls were going out. Quickly, citizens dropped what they were doing to hurry to the river's edge and view the disaster for themselves. One witness of the scene recalled that "proprietors of stores hastened to the falls, taking their clerks with them; bakers deserted their ovens, lumbermen were ordered from the mills, barbers left their customers unshorn; mechanics dropped their tools; lawyers shut up their books or stopped pleading in the courts; physicians abandoned their offices."

Responding to the emergency, citizens of St. Anthony and Minneapolis worked together to build large rafts of timber, which they floated over the whirlpool and filled with dirt, rocks and other debris until the rafts sank into the hole. Once this break was plugged, however, another hole appeared.

Throughout the day, volunteers built rafts to fill the river where the limestone bedrock had collapsed. By the afternoon, workers and spectators were walking across a network of rafts that had apparently succeeded in preventing further erosion. Then suddenly, the rafts lurched, and as people scrambled to safety, the river swallowed all of their efforts in one massive gulp. According to one local newspaper, the whirlpool in the Mississippi River "tossed huge logs as though they were mere whittlings," standing them on end "as if in sport" before swallowing them.

The failure of this initial attempt to save the falls made it clear that a more permanent solution was needed. A temporary dam was completed by the end of October 1869, while mill owners and citizens of the two cities debated long-term solutions to the problem.

During the winter and spring of 1869-1870, the St. Anthony Company worked to repair the tunnel and to protect damaged areas near its property on Hennepin Island. A flood in April 1870 destroyed these repairs. Flood water and debris raced through the old tunnel, scouring out the sandstone under the mills on the downstream end of Hennepin Island. The limestone cap soon collapsed, and several mills and other buildings fell into the river.

The progressive deterioration of the falls continued and the end of the limestone bedrock was drawing near. Without a dramatic preservation effort, St. Anthony Falls would quickly disappear.

The Corps of Engineers and the Preservation of St. Anthony Falls

The St. Paul District Office of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers had just been established three years when the Eastman Tunnel collapsed in 1869. In response to the disaster, the Corps hired an engineer, Franklin Cook, to survey the damage and recommend actions that should be taken to preserve St. Anthony Falls. At the time, the Corps had no authority from Congress to work on the falls and could not obtain such authority unless the project was related to the Corps of Engineers' navigation mission.

Cook recommended the construction of a timber apron to prevent further degeneration of the falls, as well as the construction of a dam near the edge of the waterfall to maintain a constant level of water over the limestone cap to prevent freezing and cracking.

Cook argued that the Corps should seek authorization from Congress to save the waterfall on the basis that navigation above Minneapolis would be lost if St. Anthony Falls were destroyed. Congress reluctantly accepted this argument and provided $50,000 for the Corps of Engineers to save the falls.

In August 1870, the Corps hired Cook as supervising engineer and started to work by taking over the tunnel repair project from the St. Anthony Company. The engineers also built a dam between the St. Anthony and Minneapolis millponds that extended from the upper limit of the limestone ledge to the falls. The dam was constructed of timber cribs loaded with stone and was intended to be a permanent wall around the upper breach in the Eastman tunnel.

While the Corps made significant progress, in July 1871, the engineers discovered that the tunnel was once again filling with water. After a considerable search, they found that the leak originated between Nicollet Island and the east shore of the river. Water had traveled under the new dam and had scoured a cavity 16 feet wide by 8 feet deep under the limestone. To fix this new problem, the Corps built another dam from Boom Island to Nicollet Island, cutting off water to the St. Anthony millpond.

In August 1871, another new tunnel scoured out by the river threatened the existence of the Minneapolis millpond and led the citizens of Minneapolis to raise money to repair the tunnel and build an apron to protect the foot of the falls. When this new failure occurred, the Corps of Engineers surveyed the sandstone above the limit of the limestone ledge and found it was filled with holes.

The condition of the underlying sandstone led Cook to conclude that only a wall under the limestone, extending across the entire width of the river, would save St. Anthony Falls. However, Congress had not authorized funds for such a project.

In the years between 1871 and 1874, the Corps, mill owners and private citizens labored continuously at the falls to avert one crisis after another. The Corps worked to clear debris, plug holes and line the walls of the tunnels to prevent further collapses.

In April 1873, a flood destroyed the dam on the west side of Nicollet Island, opening a gap 150 feet wide and flooding the tunnel. A month later, a great hole opened in the dam at the head of the limestone bedrock. The engineers discovered that the flood water had scoured a new channel under the limestone from its head to the Eastman tunnel.

In response to these continued but unsuccessful efforts to save St. Anthony Falls, a special federal board of engineers met in Minneapolis in April 1874 to study the situation. The board recommended the construction of a cutoff wall or dike, a new apron to protect the edge of the falls, and two dams above the falls. This time, Congress recognized the immediate need for the dike and authorized the funds needed for the project.

In July 1874, the Corps began construction of the dike. First they excavated a 75-foot-deep vertical shaft on Hennepin Island. Next they began digging a horizontal tunnel 4 feet wide and 8 feet high just below the limestone for the removal of water and excavated material. Then, the Corps began excavating for construction of the concrete wall. Building the dike proved to be a formidable challenge, as flooding, leaking and collapses occurred frequently.

By November 1876, the Corps of Engineers had completed the dike, which was 40 feet deep and 1,850 feet long. Between 1876 and 1880, the engineers also completed the apron below the falls, built two low dams above the falls to maintain a safe water level over the limestone, and constructed a sluiceway to carry logs over the falls. Between 1870 and 1885, the federal government spent $615,000 to save St. Anthony Falls.

In 1885, the Corps' work at St. Anthony Falls ended and the maintenance of the waterfall once again became the responsibility of the water power companies and the City of Minneapolis. The dike is still in place under the limestone, helping to prevent the erosion of the falls.

The Upper Harbor Project

The idea of extending navigation above St. Anthony Falls by constructing locks was first introduced by settlers in the 1850s. The city of Minneapolis and its boosters kept this idea alive over the years and continuously lobbied Congress to authorize such a project. In the Rivers and Harbors Act of August 1937, Congress approved the Upper Minneapolis Harbor Development Project, which extended the 9-Foot Channel in the Mississippi River by 4.6 miles.

The idea of extending navigation above St. Anthony Falls by constructing locks was first introduced by settlers in the 1850s. The city of Minneapolis and its boosters kept this idea alive over the years and continuously lobbied Congress to authorize such a project. In the Rivers and Harbors Act of August 1937, Congress approved the Upper Minneapolis Harbor Development Project, which extended the 9-Foot Channel in the Mississippi River by 4.6 miles.

The 9-Foot Channel Project was authorized in 1930 and completed in 1940. It included the construction of a series of 23 locks and dams on the Mississippi River between St. Louis and Red Wing, Minnesota, as well as dredging a deeper channel, to improve navigation. [Lock and Dam #1 in Minneapolis and Lock and Dam #2, at Hastings, were built in 1917 and 1930, respectively, under previous Congressional authorizations.] Prior to the construction of the Minneapolis Upper Harbor Project, the 9 Foot Channel reached only as far as the Northern Pacific Railway bridge, just upstream of Washington Avenue.

World War II, numerous economic and engineering studies, and project planning combined to delay construction of the Minneapolis Upper Harbor Project until 1948, when dredging for the project began.

The Minneapolis Upper Harbor Project included the construction of the Lower Lock and Dam (completed in 1956), the Upper Lock (completed in 1963), dredging a channel 9 feet deep and a minimum of 150 feet wide, and alterations to bridges and utilities within the project area.

The fragile geology of the St. Anthony Fall’s area and congestion due to urban development called for a departure from conventional design and construction practices for the Upper Harbor Project. In 1939, the Corps built a 1 to 50 scale model of the project site from Hennepin Avenue to the Washington Avenue Bridge at the St. Anthony Falls Hydraulic Laboratory at the University of Minnesota. Other models were also made to aid in the design of the spillway for the lower dam and the filling/emptying system for both locks.

Three railroad bridges ran through the Upper Harbor Project area. The Corps had to alter all three without discontinuing rail service. In each case, the Corps replaced part of the original bridge with a steel truss to allow the passage of river vessels.

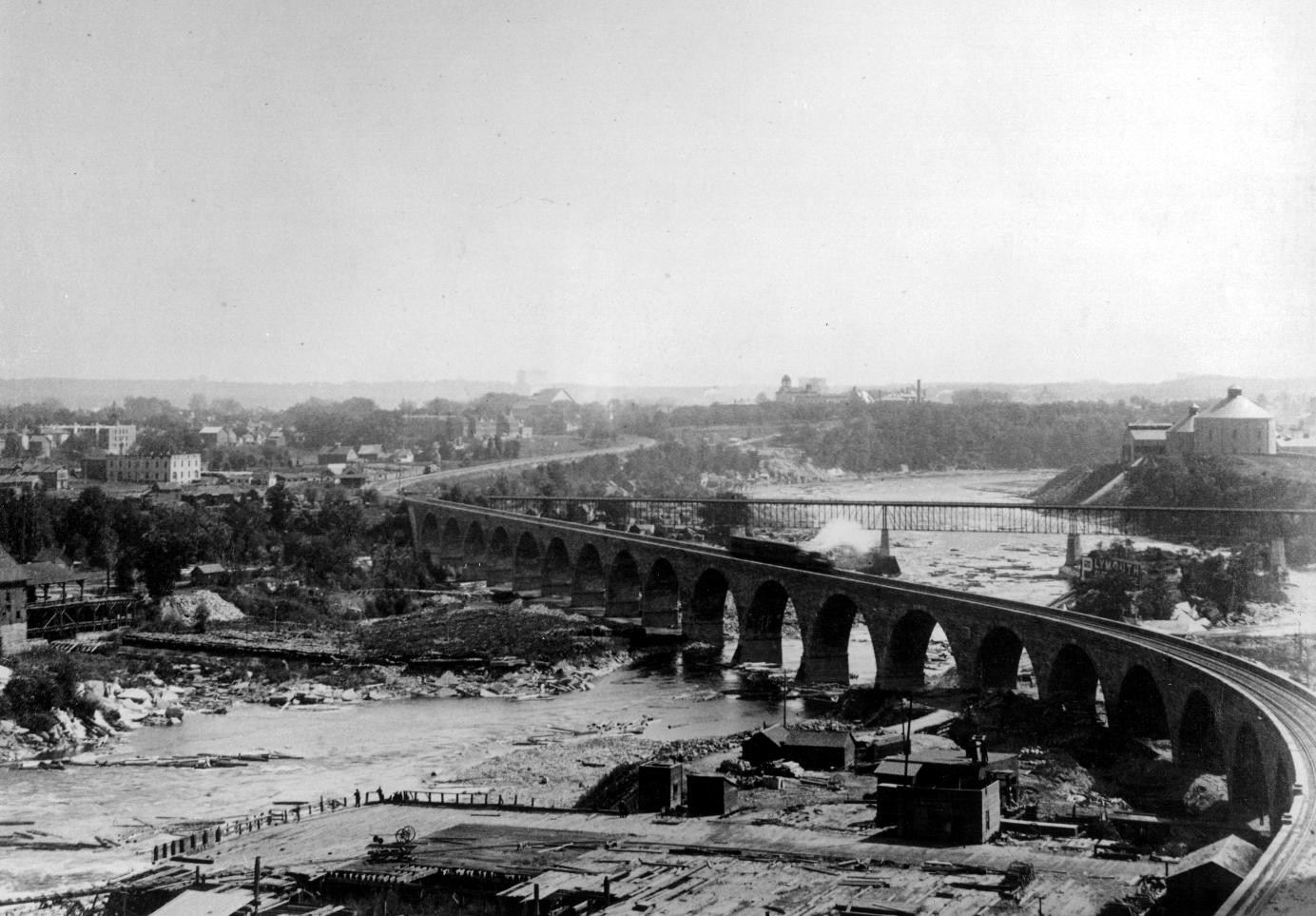

Remodeling the Great Northern Railway's historic Stone Arch Bridge presented the most complex engineering problem. Because it was not feasible to reroute the large number of trains that used the bridge, the Corps had to remove one pier and two spans of the structure without disrupting train traffic. To erect the truss and remove two arch spans under these conditions, the railroad grade was raised 5 feet and the trains were limited to the use of one track.

Remodeling the Great Northern Railway's historic Stone Arch Bridge presented the most complex engineering problem. Because it was not feasible to reroute the large number of trains that used the bridge, the Corps had to remove one pier and two spans of the structure without disrupting train traffic. To erect the truss and remove two arch spans under these conditions, the railroad grade was raised 5 feet and the trains were limited to the use of one track.

The total cost of the Upper Harbor Project was approximately $3 million. The Upper and Lower St. Anthony Falls locks make possible the navigation of numerous commercial and pleasure vessels over the Mississippi River's only waterfall. Although the project dramatically changed the appearance of the St. Anthony Falls area, it fulfilled a century-old dream to extend river navigation above Minneapolis.

Sources

John Anfinson, "The Corps of Engineers and the Preservation of St. Anthony Falls." (St. Paul District, Corps of Engineers, 1993).

Scott Anfinson, "Archaeology of the Central Minneapolis Riverfront," The Minnesota

Archaeologist (Vol. 48, Nos. 1-2, 1989).

Merlin Berg, "Abstract of Available Historical Data on St. Anthony Falls." (St. Paul District, COE, 1939).

Clarence Buending, "A Review of the Construction of the St. Anthony Falls Project." (St. Paul District, COE, 1962).

Jonathan Carver, Travels Through the Interior Parts oj North America in the Years 1766. 1767 1768. (London, 1778).

Lucile Kane, The Waterfall That Built a City. (Minnesota Historical Society, 1966).

Raymond Merritt, Creativity. Conflict and Controversy. (U.S. Government Printing Office, 1980).

Francis Mullen, "The St. Anthony Falls Navigation Project." Proceedings of the American Society of Civil Engineers (March, 1963).

Martin Nelson, "Nine-Foot Channel Extension Above St. Anthony Falls," Minnesota Engineer (June 1960).

Richard Ojakangas and Charles Matsch, Minnesota's Geology. (University of Minnesota Press, 1982).

Frederic Trautmann, editor, "A German Traveller in Minnesota Territory: Johannes Georg Kohl." Minnesota History (Winter, 1984).

Carole Zellie, "Geographic Features and Landscape Change at St. Anthony Falls." (St. Anthony Falls Heritage Board, 1989).